By: Jarrett Carter Sr. – @jlcarter_sr

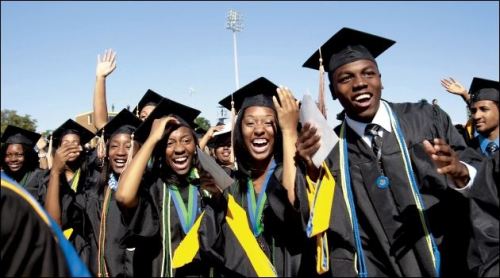

Black graduates of historically black colleges and universities feel more attached to the mission of, and relationships forged at their schools than black graduates of predominantly white institutions, according to a survey of more than 55,000 African American college graduates released yesterday by Gallup. HBCU grads also feel financially more stable, more purpose driven and more socially adjusted.

But the magic behind those numbers lies in the hearts and experiences of those who made the initial choice to enroll and to graduate from an HBCU. Others who were not raised or who did not matriculate into the HBCU experience have a harder time understanding the value of a college culture where nurturing, mentoring, fellowship and rigor make a difference across personal and professional paths of development.

So how do HBCU graduates sell a narrative that can only be seen by paying stakeholders? How do you demystify and de-stereotype schools, even as counter-narratives about HBCU inefficiency, crime and struggle grow by the day?

You go to the numbers – and not just the number of people who think HBCUs are God’s gift to America, but the numbers which illustrate industrial and financial value to cities, states and the nation.

12 – The number of HBCUs in the top 25 baccalaureate producers of African Americans who went on to earn a doctorate in science or engineering between 2002-2011.

1,445 – The total number of African Americans to earn S&E doctorates from the 12 HBCUs between 2002-2011.

19 – The combined number of corporations which gave $500,000 or more to the Thurgood Marshall College Fund and the United Negro College Fund in 2013.

$192 million – Total amount of gifts to TMCF, UNCF in 2013.

$2.5 billion – The combined economic impact of Florida A&M, North Carolina A&T, Jackson State and Tennessee State – four of the nation’s largest public flagship HBCUs – between 2010-2012.

What do the numbers mean? That in spite of the crises about enrollment, alumni giving, and cultural relevance, the nation’s S.T.E.M. industries are able to get highly-trained black researchers and innovators whom were groomed by HBCUs. It says that some of the world’s largest companies think that students who choose HBCUs are worth scholarship investment, and their institutions are worth capacity building.

And it says that HBCUs help local and state economies flourish, as a result of student, faculty and staff spending, capital project expenditures, job creation, minority business contracts awarded, and as municipal attractions through athletics.

What it doesn’t say is how HBCUs help to create opportunities for race and gender diversity in the NCAA’s Division I ranks, where African Americans and women continue to be an outgroup in athletic administration nationwide, except for on HBCU campuses.

The numbers also do not indicate how many citizens in HBCU cities have been registered to vote, how many homeless people have been fed and how many black children have been tutored by HBCU students in these communities. Those are the “known unknowns,” for which HBCUs have historically been responsible, but have rarely earned credit or support.

Surveys are great, but in the conversation about HBCU value and support, alumni can do much better with our hands and hearts around the numbers which depict a more complete narrative of our schools.